The Four Cs of Construction AI: Cost, Capability, Competence and Competition

Construction artificial intelligence in 2024: Part 1

This year has seen artificial intelligence (AI) enter the mainstream. After decades of development, new methods of machine learning (ML) led to the release in November 2022 of Chat GPT by OpenAI, followed by GPT-4 and other large language models (LLMs) like Anthropic’s Claude and Mistral in 2023. At the end of 2024 these are available through widely used software like Microsoft’s Edge and Office (with Copilot, using Chat GPT), Google’s Gemini, and Llama from Meta. New computers come with AI installed, such as Apple Intelligence, another version of Chat GPT, on Macs and iPhones.

Cloud service providers provide web access to AI as Models as a Service. Amazon Web Services has Bedrock, offering models from AI21 Labs, Anthropic, Cohere, Meta, Mistral AI, Stability AI, and Amazon for text generation, summarisation, question answering, and image recognition and generation. Companies can use their own labelled datasets or do pretraining with unlabelled data to adapt models to a specific domain or industry. Amazon SageMaker Studio has tools for preparing data and building, training, deploying and managing a ML model. Microsoft Azure offers nine models from OpenAI (Microsoft is a major investor), Phi, Cohere, Meta, Mistral, Hugging Face, Nixtla, Core 62 and Stability AI. Available in Azure AI Studio or Azure Machine Learning. Google’s Vertex AI Studio has 150+ first- party, third-party, and open-source models [1].

The actual extent of use of AI by companies rather than individuals is unclear. A US Census Bureau survey in March 2024 found ‘the fraction of firms using AI is relatively low but rising: from about 3.7% at the start of the collection in September 2023 to about 5.4% at the end of February 2024. AI use is expected to rise further to about 6.6% by Fall 2024. There is enormous variation in current use by sector from a low of 1.4% in Construction and Agriculture to a high of 18.1% in Information.’ The survey also found a much higher rate of AI use by people of 39% than by firms.

Other surveys have smaller samples. For example, the annual McKinsey chief experience officer (CXO) survey in October 2024 surveyed 276 people in five corporate functions across 18 industries in North America and Europe [2]. McKinsey claimed: ‘In less than two years, generative artificial intelligence (gen AI) has become a mainstream tool with applications across almost every area of the economy.’ However, as Figure 1 from their report shows, that claim is nonsense, as the actual level of use is 22% in these large companies for functions where AI should be most applicable (80% of companies in the survey had revenue over USD$1 billion). For small and medium size companies the use rate will be much less.

Figure 1. McKinsey CXO survey

The Deloitte August 2024 State of Generative AI report with 2,770 respondents also found limited use: ‘Generative AI efforts are still at the pilot or proof-of-concept stage, with a large majority of respondents (68%) saying their organization has moved 30% or fewer of their Generative AI experiments fully into production’. The survey included use cases for customer service and report writing from eight industries, and 42% of respondents said productivity and efficiency gains or cost reductions had been the main benefit. The survey also found employees with AI skills were paid more.

This post is divided into two parts. Part 1 below is a discussion of the current state of use of AI based software systems in construction, at this point in their deployment. It attempts to get some perspective on what is available and how construction firms have to balance the potential benefits of AI against the cost of subscribing to AI systems, how AI might improve the capability of firms, and the importance of employee competence in the skills and expertise required to use AI. It suggests AI can provide a competitive advantage for firms that successfully reduce costs with AI, and that could be from one or more specific point solutions rather than a platform. Firms will have to work with AI to survive.

Part two is a survey of companies with construction AI systems, divided into six areas: preconstruction and estimating; project and document management; site monitoring and safety; equipment management and maintenance; design and planning; and materials. It has thumbnail outlines of companies ranging from large and recognised technology leaders to startups [3]. It does not attempt to cover every new company everywhere with a construction related AI system, although this is a large and representative sample with nearly 100 companies listed.

Will Construction AI Deliver Productivity and Efficiency Gains or Cost Reduction?

Much of the commentary on construction AI is little more than marketing attached to the idea of industry ‘transformation’, often from industry observers rather than practitioners. Unsurprisingly, the websites of construction AI developers have glowing testimonials on their products. There are extravagant and exaggerated claims made, like this: Building the Future: Bluebeam AEC Technology Outlook 2025 found that 74% of AEC firms are now using AI in at least part of their projects, with 35% of respondents reporting cost savings between $100,000 and $500,000 through the use of new technologies. (BlueBeam is part of Nemetschek Group, a major software provider with Archicad and Vectorworks)

Unfortunately, there is no serious publicly available discussion from users of construction AI on the costs and benefits, beyond generalities about the potential for AI to manage tasks and solve problems like excess waste, energy use and defects, while increasing communication and coordination and reducing claims and disputes. The problem is, people in companies that are actively investigating and applying AI on their projects, if AI is delivering for them, aren’t going to tell their competitors. This could be taken as a sign that AI is in fact making a difference.

There are repetitive tasks that AI could do for almost all construction firms, like takeoffs for estimates, code compliance checks with image recognition, or using a text reader for document management. These would not require changing firms’ work processes and complement current skills. For contractors, progress tracking and site monitoring could deliver cost savings on workforce and safety management, and subcontractor supervision and payments, and reduce reporting cycles for quality control.

The important measure would be cost savings, and a contractor, supplier or subcontractor could target one task where AI can reduce costs through automating repetitive and time consuming work. In an industry with fine margins and competition for work, reducing costs with AI in one task is an advantage even if the reduction is not great, because the competitors are similar firms with the same costs. Firms will have to start working with AI somewhere, sooner rather than later, if they are to survive.

Productivity and efficiency gains are more difficult to measure. Improved communication and coordination would be a positive, and many AI systems offer that, but the actual effect on costs and project delivery may not be much. Then there is the promise that a professional (like an estimator, engineer, PM, or claims manager) would be more efficient with an AI assistant, but there is a learning curve associated with working with AI, and an assistant still has to be monitored for accuracy. Realising the potential efficiency gains from AI may take some time and require some degree of reorganisation.

This is an argument for incremental gains from adopting and learning how to use AI, rather than the breakthrough leaps in performance advocates typically claim for AI. There are two reasons why this may be the case: first, there are many elements in the final cost of a project, so improvements in one or some of those can only affect total costs at the margin; and second, while AI might deliver a cost reduction that will not come for free, because there are costs for AI subscriptions and IT resources.

That said, the extent and range of systems found in the companies included in the survey of construction AI in Part 2 of this post suggests that in the near future there will be significant productivity and efficiency gains and cost reductions for firms, regardless of size, that get their AI adoption and implementation strategy right.

Diversity Across Six Areas of Application

The diversity of construction AI offerings is striking. There are large, enterprise scale systems from major software developers like Autodesk, Bentley, Nomitech, Procore and Trimble that integrate with other software. Global contractors like AECOM, Bechtel and Skanska have been developing AI assistants and skills for several years. Then there are specialised, specific task systems, like those from equipment manufacturers for predictive maintenance, image recognition for cost estimating, reality capture for progress tracking and safety management, and generative design for architects.

The companies outlined in Part 2 are divided into six areas. The divisions are not always neat, particularly for the larger systems because there are overlapping functions, and there are subsets within the six divisions. However, this is a reasonably comprehensive if not complete survey of construction AI at the end of 2024 with a large and representative sample of nearly 100 companies. Excluded are onsite automated and robotic equipment, covered here in a previous post, and 3D printing, covered here in a 2023 post.

Preconstruction and estimating - AI is used for site layouts, submittal logs, compliance checks, takeoffs, estimating costs, bids and tenders. Two issues that AI and ML has to address are the lack of standardised industry data and extracting data from different sources, such as PDFs, BIM models and drawings. The first means companies have to build databases and rely on their own projects for data, and there are providers offering assistance with those. These systems use AI and historic data from projects for estimating costs. The second has seen development of AI for image recognition to automate quantity takeoffs from drawings, PDFs and BIM, and scanning drawings to check for missing information and risk assessment.

Project and document management – As well as AI assistants for PM and construction management there are AI systems for workforce and equipment management, claims, code and contract compliance, attendance and access, and risk management. Some PM systems combine project, site and workforce data for planning, scheduling, and task assignments.

Site monitoring and safety - Safety systems monitor sites and people using sensors, cameras and wearables like badges and detect hazards. Reality capture and computer vision matches site work to BIM models to track progress and defects, and provides access control, headcounts, timesheets and other analytics.

Predictive maintenance of construction equipment - Called telematics, these systems integrate sensors and wireless to collect and record equipment use and performance, and use AI for analysis and predictive maintenance. Typically available as a subscription service, manufacturers now install them on most new equipment and they can be retrofitted to older machines.

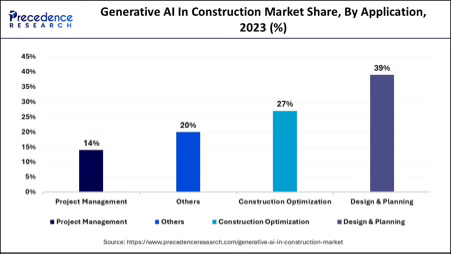

Design and planning - One of the first applications of construction AI was in design, which was already software based. Generative design systems create multiple design options according to specific criteria, by providing alternative solutions using a given set of parameters. Used to optimise a design, examples are crane positioning in site plans, site and floor plan layouts for office and apartment buildings.

Materials – there are AI applications for concrete quality control, and some country-based ones for selection of materials by designers.

It is not possible to get a good grasp on the cost of most of these systems. All are subscription based, usually but not always on the number of users, but many do not have prices on their websites. Where available, advertised monthly payments range from tens to hundreds of dollars, and subscriptions often have different options. All this makes assessing the value of different offerings difficult.

The Four Cs of AI: Cost, Capability, Competence and Competition

At this stage, for the majority of small firms in construction, AI is irrelevant for three reasons. First is the cost, which no matter how low will be too high compared to any efficiency or productivity gains or benefits they might get. That is because, second, the work they do is so small in scale and simple that AI will not improve their capability to do that work. And third, these firms typically do not have people with the skills and technological competence to use AI.

At the other extreme are the largest global construction firms. They can pay for AI systems and employ people with the necessary skills, and some have several years of experience with AI systems they have developed internally (e.g. Accionia, AECOM, Balfour Beatty, Bechtel, Skanska). For these firms, using chatbots for document search, image recognition for design and estimating, or vision systems for site monitoring and progress tracking could deliver significant efficiency and productivity gains, improving capability. If AI can increase margins or winning tenders for the megaprojects the firms compete on, their AI use and expertise will improve rapidly. Also, on large projects the cost of using one or more AI systems is not prohibitive, allowing learning by doing and trials of systems on a project by project basis.

For large national or regional contractors with a portfolio of projects, the equation is different. Although project management platforms offered by providers like Aconex, Autodesk and Procore are not cheap, these firms can afford them and most will probably already be using one or more of them, or be using other systems for design, estimating and progress tracking. Although they are unlikely to be developing AI applications internally, they have well established capex programs and IT capability. Importantly, there will be relationships with the major software providers who are incorporating AI into their products that can be built on. These firms have the scale to adopt AI and it should improve their capability, and they will be conscious of rival firms that could gain a competitive advantage through faster adoption of AI. However, they may struggle with competence because there is fierce competition for people with AI skills, and they may be reluctant to pay a premium for those skills.

There are some large US contractors that have technology strategies. Suffolk Constructions has Suffolk Technology, a subsidiary that acts as a venture capital arm and has invested in several construction AI startups [4]. DPR Construction has an internal task force working on AI and uses ML on their two decades of project data.

For medium size construction firms, AI is a more difficult proposition. Margins are thin and software expensive. They are often not using BIM or a PM platform. Employees are busy and focused on day-to-day project management. Trialling AI systems and learning by doing on their projects is challenging, and evaluating the number and diversity of offerings makes getting to a decision and committing hard. While there may be capability benefits in the medium-term, there are present competence and cost limits, and these constraints also apply to their competitors. Early adopters could gain a significant competitive advantage if they have the capital to invest in AI skills and systems.

Automated takeoff and estimating systems should save significant time and effort in preparing bids for small and medium size firms. If these systems reduce cost and improve accuracy in bidding for work, they could significantly increase the capability of contractors and subcontractors that can both afford them and use them effectively. For larger specialised subcontractors like HVAC and electrical, there are AI systems specific to their work available.

Point versus Platform

For all firms the difficult decision is what system or systems to invest in, because once committed there are significant sunk costs and switching can be painful and expensive. There is a basic choice between specific, point solutions that only do one or a few things, and a platform that does many things. The advantage of a platform is a unified solution, with a wide range of functions in one place. The problem with platforms is they are expensive, often complex, and lack flexibility. Point solutions can offer better value by addressing specific functions and doing them very well. However, for contractors where the number of point solutions used is increasing and issues of compatibility and complexity arise, a platform becomes an option.

Because platforms are large, have a range of functions, and can be integrated with other enterprise-scale software like accounting, resource management and customer management systems, they are also expensive. Major players like Autodesk, Bentley, Oracle/Aconex, Procore and Trimble have AI assisted systems that usually cover preconstruction, design, estimating and project management, and integrate with some other systems. These systems are platforms for large corporate users. Some of the new construction AI companies have developed platforms, examples are Buildpass and Smartbuild.

Conclusion

It is a well-known characteristic of the construction industry that many innovations come from suppliers, from outside the industry. In the past this particularly applied to materials and manufacturers of equipment and components, but more recently it has included IT and software suppliers. Many of those suppliers are incorporating AI into their products, and have added copilots, AI assistants and analytics to their systems. There are also many new entrants with AI applications, some with platforms but the majority targeting a specific function.

For some of these companies, their extent of use of AI is not obvious from their websites and in some cases may be more like advanced analytics and modelling, which could be sufficient for predictive maintenance for example. However, there are also systems based on chat bots and AI assistants that are clearly closer to the leading edge of AI. It is not possible to get a good grasp on the cost of these systems, many do not have prices on their websites, which makes assessing the value of different offerings difficult.

Some of the large global contractors have developed AI systems internally. Examples are Accionia with their Brion system for water management, AECOM, Balfour Beaty, Bechtel, Skanska, and Larsen & Toubro, but there will be others that have not gone public. Companies that are successfully applying AI on their projects, aren’t going to tell their competitors.

National or regional contractors are unlikely to be developing AI applications internally, but have relationships with the major software providers who are incorporating AI into their products. These firms have the scale to adopt AI and it should improve their capability, and they will be conscious of rival firms that could gain a competitive advantage through faster adoption of AI. However, they may struggle with competence because there is competition for people with AI skills.

There are repetitive tasks that AI can automate, like takeoffs for estimates, code compliance checks with image recognition, or using a text reader for document management. Progress tracking could deliver savings on subcontractor supervision and payments, and reduce reporting cycles. Reducing costs with AI in one task is an advantage, because competitors are similar firms with the same costs. Firms large and small will have to start working with AI somewhere, sooner rather than later, if they are to survive.

Chat GPT was launched in November 2022 by OpenAI, and GPT-4 in March 2023. In two years, AI has gone from being unreliable and error prone to a technology that allows firms to combine and analyse complex and diverse data. It can synthesise, summarise and interpret data, and provide predictions, insights and suggestions. However, it does not and cannot replace expertise because it also requires supervision and checking of results, and requires prompting and refinement from users.

Construction companies looking at AI have to weigh up four considerations. First is the cost of subscriptions, and whether they have to workload to pay for a platform rather than one or more point solutions. Second is how much difference AI can make to their capability to win, organise and deliver projects. Third is competence in the skills required, and whether their people have or can be trained in these. Fourth is what their competitors are doing, and whether AI can provide a competitive advantage. Cost, capability, competence and competition are the four Cs of construction AI.

[1] Progress in AI may be slowing down. A recent report in The Information said OpenAI’s new models have only incremental improvement over previous ones. Reuters quoted Ilya Sutskever, co-founder of OpenAI, saying results from scaling up pre-training have plateaued, with delays and disappointing outcomes in the race to release a large language model that outperforms GPT-4, now nearly two years old.

[2] According to Wikipedia a chief experience officer is responsible for user experience of an organisation's products and services, including software and hardware design management.

[3] Many of the startups came from Last Week in ConTech, an invaluable source of information on leading edge technology for the industry.

[4] This is a particularly good interview with Suffolk Construction CTO Jit Kee Chin.