Source: Government Response to the Review of Security of Payment Laws.

The recently announced five year pause in changes to the Australian National Construction Code (NCC) is intended to reduce the regulatory burden of compliance and updates on the industry. Industry inquiries and reports have focused on construction regulation, and argued complex and inconsistent planning and approvals processes and variations to the NCC are important factors in the industry’s lack of productivity growth.

Surprisingly, these reports have little discussion on security of payment (SOP), which is one of the most complex and controversial regulatory measures affecting the industry. SOP laws have been introduced to deal with the problem in construction of late or withheld payments, by giving parties a statutory right to claim progress payments. They mandate payment timeframes and require a payment schedule, and invalidate unfair payment terms in contracts. If a payment is late or disputed, the laws provide a dispute resolution process and facilitate adjudication. An unresolved issue is how effective SOP laws are in protecting payment owed to subcontractors and suppliers when a head contractor becomes insolvent.

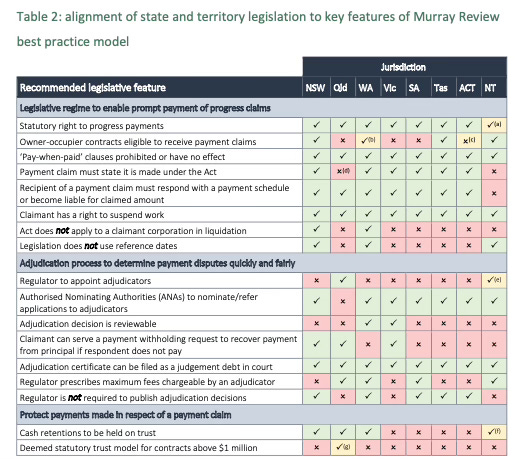

NSW was the first state to pass SOP legislation in 1999, but now all states and territories have SOP schemes. However, as the figure above shows, there are significant differences between their legislative features and how they operate, whether they have retention trusts or project bank accounts, who can be a trustee, the role of the regulator, review of adjudication decisions, and use of reference dates.

The most significant review on SOP was the 2017 Murray Report, which said ‘the hierarchical contractual chain does not enable the party at the lower part of the chain to negotiate fair and reasonable contract terms, including provisions relating to prompt payment. This has resulted in the party at the lower part of the contractual chain being unable to maintain its cash flow and thereby incurring significant financial hardship.’ Murray made 86 recommendations, including for national consistency and use of statutory trusts.

In March 2025 the Commonwealth Government released its response to the Murray review, which noted that Queensland is leading in SOP policy: ‘Some state governments have trialled project bank accounts, including Queensland, Western Australia and New South Wales. Following a trial, Western Australia now uses project bank accounts for certain government projects valued over $1.5 million. Queensland has the most expansive policy on project bank accounts, making them a central feature of recent reforms and phasing them in across the construction sector….Many other states and territories are watching the progress of the Queensland regime as a test of project bank accounts.’

This guest post on the Queensland trust account system is by Laura Hattin, from Building Trusts, a company that advises on compliance with the SOP legislation and Queensland Building and Construction Commission requirements. The company also provides training and support for construction contractors and subcontractors, suppliers of materials, services and software, and property developers. The post is a clear explanation of the system and its strengths and weaknesses, and I’d like to thank Laura for it.

The Queensland Trust Account System

What They Are

The Queensland Government introduced statutory trust accounts under the Building Industry Fairness (Security of Payment) Act 2017. The policy objective was “to help people be paid for the work that they do”.

Trust accounts are a legal requirement meaning that they are mandatory, not optional, and businesses cannot avoid them or contract out of the requirements.

There are two different types of statutory trust accounts in Queensland — Project Trusts and Retention Trusts.

Project Trust Accounts (PTAs):

are designed to protect subcontractor progress payments

the head contractor is the trustee

a separate PTA is required for each eligible project.

Retention Trust Accounts (RTAs):

are designed to protect any cash retention amounts withheld on certain projects

the contracting party (who withholds the retention) is the trustee

multiple parties within a contractual chain may each need their own RTA

only one RTA is required per contracting party, and it can hold retentions across multiple projects (Note: some trustees, choose to maintain separate RTAs for each project).

For current trustees (typically medium to large businesses), there is a reasonable expectation that they have the capacity and capability to manage these requirements. Moreover, the administrative burden is easing as systems improve and awareness increases.

Current statistics for trust accounts

As of 30 June 2025, 2,357 trust accounts have been opened. There are 428 different companies managing one or more trust accounts:

341 are head contractors

87 are Principals with an RTA only.

These account for just 0.4% of current QBCC licensees (out of 100,000+), which indicates that trust accounts impact only a small portion of the industry.

How They Work

Separate account

The trust account is a separate bank account that can only be opened at an “approved” financial institution.

There are specific naming conventions for these accounts, and it cannot be a virtual or subordinate account.

Restrictions on transactions

For PTAs, principals deposit progress payments directly into the account, and the trustee pays first-tier subcontractors from it. The trustee may withdraw their entitled share, but only after ensuring subcontractors’ entitlements are protected. Project costs like wages, overheads, or suppliers must be paid from the trustee’s business account, not directly from the PTA.

For RTAs, retentions must be deposited when withheld and remain in the account until they are due for release. Even if the trustee later becomes entitled to a portion (e.g. to cover defect rectification), the amount cannot be withdrawn until after the defects liability period.

Priority of Beneficiary Payments

Beneficiary payments always take priority.

For the PTA, although the trustee can withdraw amounts at any time, amounts may only be withdrawn if they are not liable to be paid to another party.

For the RTA, if the trustee becomes entitled to an amount that is in the retention trust account (for example they’ve fixed defects on behalf of a beneficiary), they cannot withdraw their entitlement until the end of the defects liability period.

Top up obligations

With both a PTA and RTA, the trustee must top up the account if there are insufficient funds to make a payment to a beneficiary. The top up must occur before the due date for payment, so that the party can still be paid on time.

Record keeping and reporting

Trustees must maintain a separate ledger for each trust account, recording all beneficiary entitlements and transactions. Financial institutions report trust-related transactions directly to the Queensland Building and Construction Commission (QBCC), giving regulators early visibility of compliance.

Audits and penalties

The QBCC may audit trust accounts at any time. Serious offences apply for evasion or misuse of trust funds, including heavy fines and potential imprisonment.

Phased Implementation

The introduction of Queensland’s trust account requirements has been phased in, with the eligibility criteria gradually expanding to impact more parties and projects over time. The thresholds differ depending on the type of trust account, with the current thresholds as follows.

A PTA applies to:

State Government and Hospital & Health Services projects where the contract value is $1 million or more.

Local Government and private sector projects where the contract value is $10 million or more.

An RTA applies to:

both Principals and Head Contractors who are withholding cash retentions on a PTA project.

The phased approach was intended to give industry more time to prepare and implement the changes to ensure compliance. However, the commencement of further phases has been delayed and then paused indefinitely by the State Government.

Reasons for the delay include:

Current Industry Conditions: The construction sector is facing significant financial and operational pressures. Rising costs, labour shortages, and tightening margins have made compliance more challenging.

High Rates of Insolvency: Construction insolvencies continue to rise across all states. Queensland has the third-highest rate of construction insolvencies, after NSW and Victoria. The government is considering these insolvency risks when determining future regulatory obligations.

Availability of Software to Support Compliance: Not all businesses have access to software that fully supports trust account requirements. The government recognises that industry needs better tools to meet compliance obligations efficiently.

Further Education and Awareness Required: Many smaller contractors who will be impacted in the next phases are not yet prepared. The delay allows additional time for industry education, government support, and reduction of administrative burdens.

The State Government announced the Queensland Productivity Commission (QPC) would consider the expansion of trust account requirements as part of its broader review of the construction industry.

Strengths and Weaknesses of Statutory Trusts

Strengths

They provide greater protection for subcontractors: clear records of who is owed what, separate account where money is safeguarded, first priority for payment, recognition of entitlement in the case of an insolvency.

They reduce poor cashflow management and payment practices: because of the restrictions on transactions and requirement for the trustee to top up the account, the trustee has to monitor their cashflow more effectively and they can’t get away with delayed or non-payment to subcontractors.

They improve the QBCC’s oversight and ability to intervene when a company is experiencing financial difficulty. This gives the QBCC the ability to take action against non-compliance and reduce the flow on effect to other parties that insolvency has.

They encourage industry best practice and professionalism with ensuring that written contracts are in place, business processes are streamlined, claims are recorded, responded to and paid on time and business records are in order.

Weaknesses

They can cause cashflow constraints: because of the separate accounts per project, restrictions on withdrawals, and the requirement to top up accounts, trustees don’t have the same flexibility they previously had without trusts. Instead of one business account to pay parties from and smooth out underperforming projects, trustees now need to pay closer attention to a project’s performance and the alignment of payment cycles.

They reduce the working capital a business has access to: cash retentions are no longer available to use as interest-free working capital and must be transferred into the RTA at the time of withholding from payment. These funds are locked until due to be paid and cannot be invested or withdrawn by the trustee. While trustees are entitled to the interest that accrues, the rates offered on these accounts are minimal compared to other investment opportunities or using the funds to grow the business. (Note: this is an intended consequence! Businesses do need time to build their own working capital to manage the transition to trusts).

They create additional administrative and compliance burden: managing trust accounts means opening and maintaining multiple accounts, recording trust transactions, reconciling ledgers, sending notifications, and meeting new reporting obligations. For smaller businesses, these overheads are more difficult to manage and have a bigger proportional impact on business costs than they do for larger companies. (Note: software systems have been slow to adapt and provide functionality that assist trustees with managing trusts and the additional record keeping and notification requirements).

They don’t protect everyone: only first-tier subcontractors on large private sector or government projects are currently covered by the framework. This is due to the delayed rollout of trust accounts across industry and because retention trust accounts only apply to projects requiring a PTA, rather than more broadly to any party withholding cash retentions as occurs in some other States.

Industry Reaction

General support with framework: many businesses that want to do the right thing understand and support the trust account requirements. They see the value in greater transparency, fairer payment practices, and improved protections for subcontractors.

Use it as an opportunity for positive change: for proactive businesses, trust accounts provide a chance to improve their systems and processes, manage cashflow more effectively, and place greater importance on compliance, trust, and transparency with the parties they work with.

Frustration with administrative burden: there has been a lack of support from software providers and a slow rollout of system updates. Without integrated tools, businesses have found it harder and more time-consuming to manage the trust requirements. Software companies have also been hesitant to invest in changes as the rules currently affect only a small proportion of their user base.

Challenges with initial set-up: opening and operating a first trust account requires major changes to systems, processes, and knowledge. It often takes time for businesses to fully understand the rules and embed them into day-to-day operations. Many businesses are also reluctant to invest in changes ahead of needing their first trust account.

Frustration with lack of support: there is limited information and education available. While the QBCC provides general resources online, many businesses find these lack the practical detail needed to apply the requirements effectively.

Varied views across government and industry bodies: trust accounts remain politically contentious. With the recent change in Government, there are ongoing debates and recommendations about whether deregulation is needed to improve productivity in the industry.

Mixed perspectives on fairness: some businesses argue it is unfair that the rules apply to all when only a small proportion of parties engage in poor payment practices. Others view the framework as an opportunity to strengthen business practices and weed out unscrupulous operators. However, concerns remain about behaviours such as pushing down contractual risk, delaying payments, or refusing to pay subcontractors when problems arise from the builder’s own pricing or margin management.

Issues with Insolvencies

The general problem is that, without trust accounts, subcontractors are left entirely unprotected in an insolvency. They are unsecured creditors and usually recover little to nothing of what they are owed. While statutory trust accounts provide a much stronger safeguard by ensuring subcontractor entitlements are clearly recorded, kept separate, and legally prioritised, there are still gaps when the business itself has collapsed. In particular:

PTAs operate as transaction accounts, so by the time of insolvency there is usually nothing left in them.

RTAs usually still hold funds, but recovery can be delayed if administrators cannot release them due to insufficient funds for their own costs.

Even with these limitations, trust accounts remain the only mechanism that ensures subcontractors have a statutory right to payment in the event of insolvency. They significantly increase the likelihood of subcontractors being paid compared to the alternative, which is virtually no recovery at all.

It could be argued that the structure of trust accounts, particularly the restrictions placed on a company’s access to cash flow, encourages earlier intervention when a business is under financial stress. Rather than continuing to trade while insolvent and accumulating more debt, trust account requirements prompt companies to act sooner.

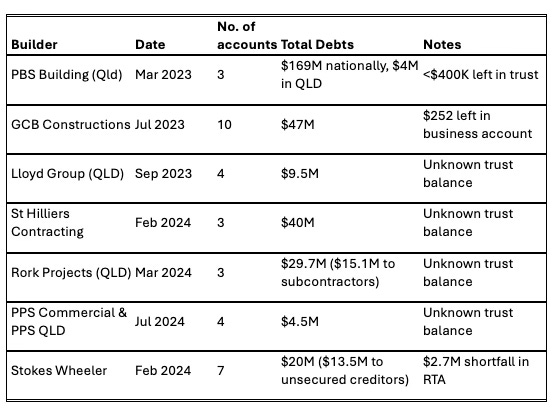

Table 1. Queensland insolvencies since the introduction of statutory trusts

In the Stokes Wheeler case, it was reported that the QBCC requested an updated financial report after receiving regular data from financial institutions about trust account balances, particularly concerning the RTA. This early visibility likely prompted the company to enter voluntary administration. This demonstrates the value of ongoing oversight through trust account reporting, compared to relying solely on annual financial reporting. With Stokes Wheeler, it will be interesting to see what action the QBCC takes as the builder deliberately misappropriated funds, and whether the subcontractors end up with payment of outstanding retention funds that they have a statutory right to, whether or not the money is there.

PBS insolvency

PBS Building was the was the first insolvency where trust accounts were in place, and the QBCC’s first trust account prosecution. PBS had three PTAs and one overarching RTA at the time of administration. The developer, Stockland Kawana Waters, was fined $150,000 because they failed to deposit funds into the PTA when paying the head contractor — not once, but 12 times, even after receiving two warnings from the QBCC.

When the PBS group of companies collapsed they owed more than $169 million to creditors, including approximately $55 million to subcontractors and suppliers. In Queensland, PBS Building (Qld) owed over $4 million to subcontractors, yet the project trust accounts held less than $400,000. A total of $3.9 million had been paid outside the trust account for the Bokarina Beach project.

The administrators applied to the Supreme Court for directions on releasing trust funds to beneficiaries, but later sought guidance on whether they could access any of the trust funds to cover their own fees, as there were insufficient assets left in the business. The court found that the Building Industry Fairness (Security of Payment) Act 2017 (Qld) prevents such remuneration until all subcontractors had been paid. This left the funds effectively “stuck” as the administrators were unwilling to perform the work without payment, and subcontractors remained unpaid. The case highlighted a structural weakness in the system. A copy of the judgment is here.

Broader Security of Payment Measures in QLD

There are other broader security of payment measures in QLD that are designed to improve payment practices and ensure parties are paid for the work they perform. These include maximum timeframes for payment, invalidation of “paid when paid” clauses, default payment periods, automatic reference dates for claims, obligations to respond to claims if payment will not be made in full, and faster dispute resolution processes such as adjudication. There are also enforcement mechanisms such as the right to suspend works, commence legal proceedings, issue payment withholding requests, or lodge subcontractors’ charges if a party remains unpaid.

However, none of these measures provide protection in the event of insolvency. Subcontractors are typically left as unsecured creditors, recovering little or nothing of what they are owed. Trust accounts are the only mechanism that safeguard entitlements in insolvency by recording them clearly and providing subcontractors with a statutory right to payment.

The Queensland Government is aware of issues that arise when there are insufficient funds left in the business to cover administrator fees, and has undertaken a detailed investigation with options proposed to address it.

QPC Recommendation to Pause Trust Rollout/Investigate Further

The Queensland Productivity Commission was tasked with reviewing the construction industry and looking at ways that productivity can be improved. In the Commission’s interim report, recommendations are that the pause on further rollout of trust accounts remains in place until a full regulatory impact analysis is completed. The Commission is seeking feedback on the costs and benefits of trust accounts, their impact on cashflow and project delivery, their effectiveness in reducing non-payment, and the adequacy of technological solutions to support compliance.

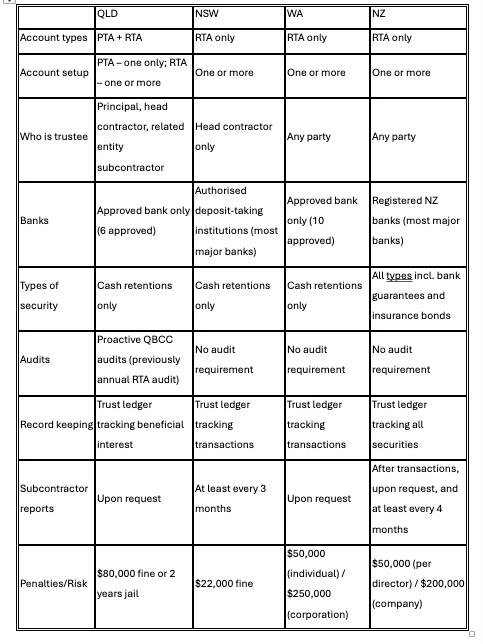

Other States and Jurisdictions

Queensland is the only State that has broader project trust account requirements. Other States and jurisdictions have a retention trust model or have/are trialling PBAs for certain Government projects.

NSW – RTAs are required on projects valued at $20 million or more, applying only to head contractors.

WA – RTAs apply much more broadly, covering projects valued at $20,000 or more, with obligations extending to any party holding retentions.

NZ – RTAs cover all instances where a security is held, including cash retentions, bank guarantees, and insurance bonds.

VIC – is considering a cascading trust model and an interim RTA requirement, though these are still under review.

Table 2. High level comparison of SOP legislation

Conclusion

The industry has been unregulated in regard to payment practices for too long. Poor financial management practices, utilising money that is ultimately owed to others, using the power that they have in the contractual relationship and having access to funds to use as working capital that is interest free. It has encouraged and enabled parties to take more risk, grow more rapidly than they may be prepared for and caused significant financial hardship and harm to others that have borne the brunt of their mistakes and costly risks.

The reality for the industry is that builders are often stretched and focused on solving immediate problems rather than investing in long-term sustainability, and legitimately question whether SOP requirements will stay or will go ahead, as there have been many changes and last-minute delays to the requirements. This makes it difficult or not worthwhile for businesses to prepare, particularly regarding the impact on cashflow and internal systems. Further, builders are often hesitant to seek advice from the QBCC. Either they don’t receive timely answers, the advice is not practical or helpful or they worry about exposing themselves to further scrutiny and risk, especially if they’re genuinely trying to get it right but are unsure of the requirements.

Another problem is that software providers have been reluctant to invest in upgrades to support trust account record-keeping. This is due to the relatively small percentage of their customer base currently impacted in QLD and the uncertainty caused by the shifting rollout dates and changing requirements.

Trust accounts are the only safeguard in the event of an insolvency that increases the likelihood of subcontractors being paid for work already performed. Typically, there are no funds remaining in Project Trust Accounts (PTAs) upon insolvency, as these are designed to operate as transaction accounts with money flowing in and out regularly. This is as intended. In contrast, sufficient funds have been retained in Retention Trust Accounts (RTAs), except for the Stokes Wheeler case. There have, however, been challenges in releasing RTA funds to beneficiaries where there are insufficient funds in the business to cover administrator fees.

Without trust accounts, subcontractors remain unsecured creditors with little to no possibility of recovery. Retention trust accounts should apply to all parties who withhold cash retentions, including builders who only work on residential projects. If money owed to another party is withheld, it should be held safely and securely in trust, regardless of project type or contract value. This raises concerns about cash flow impacts on smaller businesses. However:

Using cash retentions is optional. Businesses can choose alternative security mechanisms.

Where internal capacity or capability is lacking, trust administration can be outsourced, similar to how many small businesses already engage accountants.

RTAs are simpler to manage than PTAs in terms of flow of funds and record-keeping.

Affordable trust accounting software is now available and can work alongside existing small business systems.

What is critical is practical training and education for the industry, particularly on financial management, rights and obligations under security of payment legislation, and how trust accounts work in practice. Trust accounts are not unnecessary red tape - they help to shift the industry towards timely payment, better business practices, and long-term productivity improvement.

Appendix: Relevant Background Material

PBA Review Report (published March 2019) – an independent review of the SOP framework in QLD implemented under the Building Industry Fairness Act in 2017. This led to significant changes from the PBA model of three separate accounts per project to the Trust Account framework that is in place today.

John Murray Report (published December 2017) – a Federal Government Review into construction industry payment practices and how to ensure that subcontractors are paid for the work that they do – it recommends a deemed statutory trust model.

Government response to the John Murray Report (published March 2025, more than 7 years after the original report was released) – it acknowledges the merit in PBAs (interim solution) and deemed statutory trusts (long term solution) for protecting subcontractor payments in the industry, but ultimately cites a number of practical and economic concerns so it is not supporting the introduction of them at this time.

Bruce Collins Report (published November 2012) – an older NSW Government Report recommending statutory trusts.

Thanks again to Laura for this interesting and relevant post, which as the first guest post here is most welcome. If anyone would like to contribute a post please message me on LinkedIn or email gerard.devalence@gmail.com.